Eleven solar thermal farms have been proposed for Southern California and are going through the permitting process with the California Energy Commission and with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management if on federal land. The 11 farms are among the biggest of the almost 50 renewable energy projects seeking to begin construction in California before the end of the year so they can seek federal stimulus funds.

The company proposed a 2,000-acre solar farm, named Beacon, on fallow agricultural land on the edge of California's Mojave Desert. The site has the great desert sun but is on degraded land near a freeway, an auto test track and old buildings.

The site "is exactly where solar should be," says David Myers, head of conservation group Wildlands Conservancy.

The site "is exactly where solar should be," says David Myers, head of conservation group Wildlands Conservancy.But two years later, NextEra still awaits permission to begin construction from the California Energy Commission, which grants permits on such projects after environmental reviews. Time is running short, not only for NextEra but for several dozen green-energy projects in California. Ground must be broken on them before year's end to get federal stimulus funds worth 30% of the projects' cost.

The deadline — and the push for green energy by President Obama and California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger— has inspired unprecedented coordination among regulators and environmentalists who want green energy but not rampant destruction of wilderness. If they succeed in siting so many large solar projects quickly, California may set a precedent for how other states resolve concerns over land use vs. the benefits of green energy.

"It's a scene that's being played out all over the country," says Benjamin Kelahan, senior vice president for energy of the Saint Consulting Group. But California, he says, is "a hotbed of activity."

Yet the sheer number and size of the California projects, especially a dozen huge solar farms unlike anything regulators have reviewed in 20 years, is stressing agencies and stakeholders alike. No other state has so many huge solar projects in the pipeline. Billions of dollars in stimulus funds ride on whether the permitting process can be sped up without sacrificing California's stringent environmental standards.

No corners are being cut, regulators say. But some environmentalists fear that the tight deadlines will lead to projects that could've been better with more time. And companies say that some projects, like NextEra's, have suffered delays born of inefficient permitting.

"These are large projects at a scale we've never seen before on a time schedule that's never been done before," says Kimberley Delfino, California program director for the environmental group Defenders of Wildlife. "This is not going to be an easy thing to do."

Promise of power, jobs

If all are built, the 49 projects seeking stimulus funding would generate 11,000 megawatts of electricity a year. That's enough to supply 7 million California homes and give California utilities a big boost in meeting mandates to get 33% of their energy from renewable sources by 2020.

The projects also would drive 10,000 construction jobs, 2,200 operational jobs and up to $30 billion in investment, including up to $10 billion in federal stimulus dollars, says Michael Picker, Schwarzenegger's renewable-energy adviser.

Twenty-two of the 49 projects account for 83% of the power. Some projects fall under the permitting process of counties. But the vast majority of the large solar projects fall under the review of the California Energy Commission and, if the projects are on federal land, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

California and federal regulators are working under conditions far from the norm.

Typically, the California Energy Commission rules on seven power plants a year, most often 20- to 40-acre natural-gas plants. This year, it has almost three dozen projects to review, including 11 large solar farms, several of which will each cover 10 square miles of land. Some projects that would normally take two years to review are seeking eight- to nine-month turnarounds, says Tom Pogacnik, a deputy state director for the Bureau of Land Management.

Never before have the bureau and the commission worked so closely to coordinate and expedite project reviews, says Terrence O'Brien, commission deputy director. He's dubbed a fourth-floor conference room a "war room," where staffers meet weekly to set priorities.

In November, commission staffer Christopher Meyer noted that the staff was already "sort of at a breaking point" with the workload, a transcript of a hearing on one of the solar farms says.

More people have since been hired. At the commission, 110 employees work on siting projects, up 25% since the fall. And while other state workers face furloughs on some Fridays, a consequence of California's budget woes, "We're working," O'Brien says.

The agencies are "tearing their hair out," says Peter Weiner, who, at law firm Paul Hastings, represents solar developers.

Moving too fast or too slow?

Whether the permitting process is fast or slow, complete or subpar depends on who's talking — and when.

In January, NextEra thought its chances were "grim" to get the $1 billion Beacon project through the process in time to qualify for $300 million in federal cash grants that are given instead of tax credits as part of the stimulus program, says Matthew Handel, NextEra vice president.

At a January hearing before the California Energy Commission, NextEra unfurled a string of complaints about the process. The Beacon site had to have a plan to relocate desert tortoises, although the site "has no desert tortoises," NextEra's Scott Busa said. The company had to redo a plan five times to monitor ravens that prey on baby tortoises, although the solar fields would draw fewer ravens than the sheep that currently graze and sometimes die on the land, providing a "raven buffet," Busa said.

He also said state regulators gave NextEra a 382-day plan to offset any effect on Native American cultural resources on the site, when the company didn't have 382 days before it had to break ground to get stimulus funding.

He also said state regulators gave NextEra a 382-day plan to offset any effect on Native American cultural resources on the site, when the company didn't have 382 days before it had to break ground to get stimulus funding.Given that the site was considered almost "perfect" for solar, Busa said, "I wonder why we're here two years later?"

After the hearing, the state reduced some demands. For instance, it cut the 382-day plan to 180 days by reducing how much land needed to be surveyed, Busa says. "They've recognized they're under time constraints," he says.

NextEra, a subsidiary of the Florida-based FPL Group energy company, is now optimistic the project will make the Dec. 31 deadline.

The commission's O'Brien says he also wishes that Beacon's review had gone faster. But he says part of the blame rests with NextEra, which at first proposed using fresh groundwater despite commission opposition. "It wasn't a perfect project, and it took time to resolve the issues," O'Brien says.

Home to threatened species

NextEra is proposing one of 11 large solar thermal farms. The farms concentrate the sun's power on mirrors to produce heat used to generate electricity. They'll cover thousands of acres, many of them largely untouched desert. The region has the most intense sun in North America, but it's also home to threatened species, such as the desert tortoise, and rare plants.

Environmentalists, who're largely supportive of solar, still worry that environmental reviews will be rushed.

"We need to proceed with caution, and what the stimulus deadline has done is remove our ability to do that," says Gloria Smith, an attorney for the Sierra Club in San Francisco.

Last week, the Sierra Club faced a two-day deadline to respond to information presented at an all-day hearing on one solar farm. After it complained, the response time was set at eight business days. Typically, it'd be weeks, Smith says.

Some agency reports also lack information they'd normally have, says Joshua Basofin, California representative for Defenders of Wildlife. This month, the commission and the Bureau of Land Management filed their joint environmental review on the 6,500-acre Blythe Solar Power Project. At the filing, numerous issues were unresolved, including relocating desert tortoises and offsetting damage to burrowing owl habitat and Native American cultural resources.

"We're very concerned that there hasn't been comprehensive environmental analysis for some of these projects," Basofin says.

The commission's O'Brien says environmental reviews will be complete. If first reports lack data, the agencies will file supplements, he says.

Several of the projects have changed to reduce their effects on the environment. The Ivanpah solar farm, at 3,500 acres, shrank 12% to lessen damage to desert tortoise and rare plant habitat. The Imperial Valley Solar farm, at 6,000-acres, is 16% smaller than originally proposed to avoid an area especially rich in Native American resources around land that was once an ancient lake.

Next few months are critical

Project developers are hopeful that the deadline for 30% cash grants will be extended, as Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., has proposed in legislation. "But nobody wants to count on an extension," says Sean Gallagher, vice president of Tessera Solar, which has two projects. The stimulus funds "are a critical part of the financing," Gallagher adds.

The next few months are also critical. Companies need permits by fall to have time to finalize financing and transmission plans. Picker, of the governor's office, expects up to 75% of the larger projects will get permits in time.

While some environmentalists say those may not be as well-designed as they could be, leading groups also recognize that land conservation isn't the only factor to consider. Global warming will degrade even pristine land, says environmentalist Delfino. Greener energy is a way to fight back, leading her to conclude that some habitat destruction is worth a bigger "long-term" gain.

"But we cannot have the cure be worse than the disease," Delfino says.

Space is the next frontier in adventure travel, suggests a survey analysis, with sub-orbital tourism perhaps embracing the modern-day jet set this year.

Space is the next frontier in adventure travel, suggests a survey analysis, with sub-orbital tourism perhaps embracing the modern-day jet set this year.In the current Acta Astronautica journal, Véronique Ziliotto of Holland's European Space Research and Technology Centre, looks at recent polls and industry estimates to reckon the chances of space tourism getting off the ground. Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo effort, in particular, looks to start flights as soon as this year, she notes, and already has about 200 flight reservations.

"In 2003, luxury travel had 20 million customers globally and generated 91 billion in revenue, which represents 20% of tourism revenues worldwide. This large untapped market represents a unique chance for space tourism," Ziliotto writes. Since then, she adds, "(t)hanks to recent technological achievements such as Burt Rutan's SpaceShipOne in 2004, Bigelow's Genesis I in July 2006 and Genesis II in July 2007 and the success of space adventures' flights to the ISS, space tourism is leaving the realm of science-fiction." The Bigelow Genesis I inflatable space station prototype made its 10,000th orbit of Earth in 2008.

A 2006 Futron Corporation poll of millionaires, asking them about their interest in Virgin Galactic sub-orbital space flights, found that "estimated demand for the year 2021 would be over 13,000 passengers, generating revenues in excess of US$600 million." Tickets would be $200,000 the first three years, and then drop to $50,000 thereafter. A second "adventurer's" survey that year found less demand until tickets dropped to $50,000; many of the customers preferred to wait for moon trips, not currently envisioned by space tourism firms.

A 2006 Futron Corporation poll of millionaires, asking them about their interest in Virgin Galactic sub-orbital space flights, found that "estimated demand for the year 2021 would be over 13,000 passengers, generating revenues in excess of US$600 million." Tickets would be $200,000 the first three years, and then drop to $50,000 thereafter. A second "adventurer's" survey that year found less demand until tickets dropped to $50,000; many of the customers preferred to wait for moon trips, not currently envisioned by space tourism firms.

More recently, one aerospace firm estimated the demand for space flights at 13,000 to 15,000 passengers per year. "In this case, the market would not be limited by demand but by the number of attractive locations for spaceports on Earth that permit a safe integration of spacecrafts in the local air traffic," Ziliotto writes.

"Promises made to public that in some future, ordinary people may experience most of the feelings of professional astronauts by simply booking a seat in a privately operated spaceship, appear today credible to some operators," says France's Christophe Bonnal of the

CNES–Launcher Directorate, in an editorial accompanying the analysis. "The hurdles are nevertheless quite significant in all domains, technical, legal, medical, insurance, and even when solved, the viability of the market will have to be demonstrated. Today, one can say we still have more questions than answers."

CNES–Launcher Directorate, in an editorial accompanying the analysis. "The hurdles are nevertheless quite significant in all domains, technical, legal, medical, insurance, and even when solved, the viability of the market will have to be demonstrated. Today, one can say we still have more questions than answers."Legal and regulatory hurdles "are undoubtedly among the most severe constraints today", he adds, particularly outside the USA. A space symposium in France last looked at the demand for space tourism in 2008, he notes, prior to the current severe economic downturn.

"The commercial future of suborbital space travel is deemed promising and the interest in private spaceflight has built up during the last few years," concludes Ziliotto. "Nevertheless, it still faces major challenges and winning the potential customers' confidence about the safety of the flights is not the least one. An accident in the early phases of commercial operation could bring the industry to a halt and jeopardize its future."

The ancient Cambodian capital of Angkor Wat suffered decades of drought interspersed with monsoon lashings that doomed the city six centuries ago, suggests a Monday tree-ring study.

A 979-year record of tree rings taken from Vietnam's highlands, released by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal and led by Brendan Buckley of Columbia University, finds the, "Angkor droughts were of a duration and severity that would have impacted the sprawling city's water supply and agricultural productivity, while high-magnitude monsoon years damaged its water control infrastructure."

A 979-year record of tree rings taken from Vietnam's highlands, released by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal and led by Brendan Buckley of Columbia University, finds the, "Angkor droughts were of a duration and severity that would have impacted the sprawling city's water supply and agricultural productivity, while high-magnitude monsoon years damaged its water control infrastructure."Alternating effects of El Nino and La Nina conditions in the Pacific Ocean, as the northern hemisphere shifted a period of medieval warmth to the "Little Ice Age" of the 17th Century, may have whipsawed the region where Angkor Wat once stood. The "hydraulic city", center of the Khmer empire from the 9th to the 15th Century, was built of impressive temples standing amid nearly 400 square miles of canals and reservoirs called "baray", according to a 2009 Journal of Environmental Management study.

Many of those canals and baray appear silted up by drought, says the PNAS paper, which left them wide open for flooding from the intense monsoons of the early 15th century. "Much like the Classic Maya cities in Mesoamerica in the period of their ninth century 'collapse' and the implicated climate crisis, Angkor declined from a level of high complexity and regional hegemony after the droughts of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries," says the study. " The temple of Angkor Wat itself, however, survived as a Buddhist monastery to the present day."

Many of those canals and baray appear silted up by drought, says the PNAS paper, which left them wide open for flooding from the intense monsoons of the early 15th century. "Much like the Classic Maya cities in Mesoamerica in the period of their ninth century 'collapse' and the implicated climate crisis, Angkor declined from a level of high complexity and regional hegemony after the droughts of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries," says the study. " The temple of Angkor Wat itself, however, survived as a Buddhist monastery to the present day."A 2005 Journal of Archaeological Science study found that a typical Angkor temple may have taken more than a century to build.

While some scholars suggest that trade interests led to the capital moving to Phnom Penh in the mega-monsoon era, the study concludes, "decades of weakened summer monsoon rainfall, punctuated by abrupt and extreme wet episodes that likely brought severe flooding that damaged flood-control infrastructure, must now be considered an additional, important, and significant stressor occurring during a period of decline. Interrelated infrastructural, economic, and geopolitical stresses had made Angkor vulnerable to climate change and limited its capacity to adapt to changing circumstances."

"Last year during a night survey monitoring biodiversity along the gallery forest of Ranobe near Toliara...Charlie Gardner and Louise Jasper came across a giant mouse lemur (Mirza) foraging within fruiting ficus" trees, WWF said in information released with this photograph.

Two species of giant mouse lemurs are known: Mirza coquereli and Mirza zaza.

Mirza coquereli (Coquerel's mouse lemur) is found in the southwestern spiny forest eco-region, but has never been seen in the Toliara area before, WWF said.

Coquerel's mouse lemurs are Near Threatened according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which means that they might qualify for vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered in the near future.

"Their population trend is decreasing. The discovery of a new population is exciting as it raises hopes for the species' survival," said WWF, which is a Switzerland-based conservation organization.

New species?

The species seen in the Ranobe gallery forest exhibits "significant differences in the coloration of its coat from the other two species," according to the researcher Charlie Gardner, who is from the University of Kent. He and Jasper were working on a project for WWF when they spotted the giant mouse lemur.

"The specimen that we observed appears to have a lighter dorsal coloration than is noted for M. coquereli, and has conspicuous reddish or rusty patches on the dorsal surface of the distal ends of both fore and hind-limbs. The ventral pelage is also conspicuously light in color, and the animal possesses a strikingly red tail, also becoming darker at the end."

"This is to suggest that it may not only be a new population, but a new species or subspecies," Gardner said. However, the animal has to be trapped, examined and tested before it can be officially described as a new species, he added.

"These findings not only highlight the biological importance of the area, but also emphasise how little we know about these rapidly disappearing forests."

"These findings not only highlight the biological importance of the area, but also emphasise how little we know about these rapidly disappearing forests. Without the creation of new protected areas, we would risk losing species to extinction before they have even been discovered or described," WWF said.

"These animals, in turn, can attract tourism and conservation revenue to the site which can help local communities to find less destructive ways to meet their development needs."

This new lemur population is not the first exciting discovery from Ranobe in recent years, according to WWF.

In 2005 scientists described the rediscovery of Mungotictis decemlineata lineata, a subspecies of the narrow-striped mongoose that had not been observed since 1915, and which was only ever known from a single specimen. This subspecies may be entirely restricted to a protected area in Ranobe.

The representative of the new Mirza population was discovered just outside the limits of the protected area, WWF said. "It highlights the critical need to extend the limits of this protected area."

The protected area, known as PK32-Ranobe[ML1] , is co-managed by WWF and the inter-communal association MITOIMAFI. It received temporary protection status in December 2008. "However, due to the presence of mining concessions, the limits of the protected area did not extend to include the gallery forests of Ranobe," WWF said.

"It is a hotspot of biodiversity clamped on almost all sides by mining concessions."

"It is a hotspot of biodiversity clamped on almost all sides by mining concessions. WWF is currently applying for the extension of the PA to include more key habitats within the decree of definitive protection," Malika Virah-Sawmy, WWF's Terrestrial Programme Coordinator in Madagascar said.

"Every year, large areas of Ranobe forests are felled by charcoal sellers, and in the past, much of the region was granted for mining concessions for the various minerals deposited in its rich sand soils. Meagre crops of maize are also planted on the calcareous soils, after felling and burning the forests," WWF said.

The new protected area is part of a new philosophy promoted by WWF for the Durban Vision which aims to triple the surface area of Madagascar protected areas, the conservation group said. "WWF aims to empower communities to co-manage PA and to find ways for communities to benefit economically protecting their environment."

Gardner's research, based at the University of Kent, is focused on reconciling conservation and sustainable rural development within new protected areas. This research will inform the management of PK32-Ranobe, allowing the identification of win-win scenarios that benefit all stakeholders, WWF said.

"We hope the area will not only represent the single most important conservation area within the Spiny forest, but also a place where communities are benefiting from conservation through ecotourism and other sustainable livelihoods," said Virah-Sawmy.

Google's decision this week to close its self-censored Internet search service in mainland China was provoking diverse reactions here Thursday.

Google's decision this week to close its self-censored Internet search service in mainland China was provoking diverse reactions here Thursday."I'm very disappointed about Google's departure as I hoped they would stay," says Professor Stan Li, who runs biometrics and security research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The majority of Chinese Internet users responded more like tour guide Li Wenwen: "I never look at political or sensitive sites," says Li, 20,

China employs an array of censorship tools widely known here as the "Great Firewall." Perhaps the most effective method is the self-censorship that media organizations here, including Google until Monday, accept as the price of doing business.

Google stopped censoring its search results Monday because it said it was the target of hacking attacks originating from China. Google now redirects "Google.cn" traffic to its Hong Kong-based site, which it does not censor. Hong Kong is a Chinese territory that is semiautonomous because of its past as a British colony.

On Thursday, some Google searches produced the same results whether from Beijing or Hong Kong. Among them is "Michael Jackson;" another is "Taiwan," which considers itself separate from China and that China considers its own.

On Thursday, some Google searches produced the same results whether from Beijing or Hong Kong. Among them is "Michael Jackson;" another is "Taiwan," which considers itself separate from China and that China considers its own.Type "Falun Gong" in Chinese into Google's search engine from Beijing, and the Web browser suddenly becomes unresponsive. Make the same search from Hong Kong and you'll get many links to the spiritual movement banned by the Chinese government.

China maintained Thursday that Google is acting on orders from the U.S. government. Ding Yifan, a development researcher affiliated with China's Cabinet, said in the China Daily newspaper that Google's exit "is a deliberate plot," part of "Washington's political games with China."

The State Department has said it was not involved in Google's decision, though Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton championed Internet freedom in a recent speech. Congress has appropriated $35 million for grants to develop technology that helps circumvent Internet censorship.

Li, the professor, says the Chinese government puts too many restrictions on the Internet.

"I think they should reconsider and make some changes, like less restrictions," he says.

Some Chinese use proxy servers to get around censorship. Most just use state-sanctioned search engines.

"Baidu is quicker and more convenient," Li, the tour guide, says of China's largest search engine.

Flowers and tributes have been left by a stream of people outside Google's Beijing headquarters. Taxi driver Tian Liang will not be leaving a bouquet. "There's fierce competition in this area. I think that's why Google leaves China," says Tian, 40. "I don't like the foreign companies who use politics as an excuse for their commercial interests."

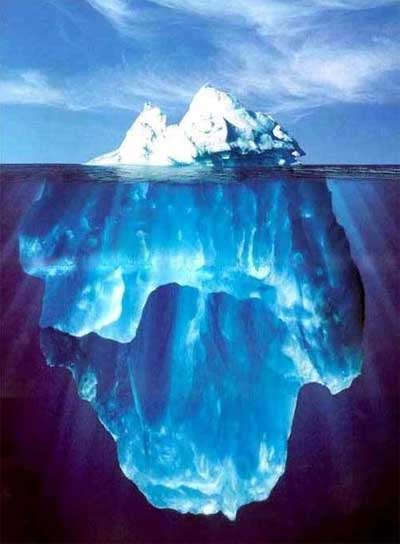

The cold waters near Antarctica are filled with lush forests of 4 main species of large algae plants, or seaweeds.

The cold waters near Antarctica are filled with lush forests of 4 main species of large algae plants, or seaweeds.Researchers are comparing their pervasiveness to giant kelp forests of the more temperate Pacific coast of California.

SOUNDBITE: Chuck Amsler, Phycologist, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham: “You enter these dense forests. They rise up 3 or 4 feet off the bottom just carpeting the bottom.”

Researchers have found the plants and invertebrates in this region produce defensive chemicals, and some are under study for the treatment of at least one type of cancer.

Researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham are in the midst of a 3-month diving expedition to the frozen continent.

The video, shot by lead researcher Chuck Amsler, shows lush growths below the ocean surface along the western side of Antarctica’s peninsula.

SOUNDBITE: Chuck Amsler, Phycologist, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham: “You don’t think about there being forests in Antarctica. But there truly are these forests of giant seaweeds underneath the surface of the water.”

The large brown algae forest includes one species that can grow up to 50 feet in length and up to 4 feet wide. These lie on the bottom, at a depth of 100 feet and more, and cover the floor nearly 100 percent in some areas.

Another brown macroalgae, or seaweed, has small spherical gas-filled bladders to make it buoyant, and the 6 foot tall plants stay upright.

Smaller algae grows at shallower depths, but still, often covers the sea floor.

These lush Antarctic forests are different from their counterparts in warmer climates.

SOUNDBITE: Chuck Amsler, Phycologist, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham: “And what’s unusual compared to other large forests of algae in other places in the world, is that these forests of algae are chemically defended. They are using compounds to make them taste bad.”

By tasting bad, large algae doesn’t get eaten by other organisms. They feast on smaller algae, and that in turn keeps the small algae from encroaching on the big algae.

By tasting bad, large algae doesn’t get eaten by other organisms. They feast on smaller algae, and that in turn keeps the small algae from encroaching on the big algae.Then, besides the forests, there is other thriving life in these cold waters.

SOUNDBITE: Chuck Amsler, Phycologist, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham: “There are lots of very steep shores, where especially when we get down deep, we get to be on pretty much vertical walls. And when you’re on vertical walls, and there are overhangs and things, the big seaweeds don’t do as well. And that’s where we can start to find really lush and really diverse communities of sponges and colonial sea squirts or tunicates, soft corals, you don’t think about corals, and it’s not hard re-forming corals but gorgonian and soft corals. And they will cover nearly a 100 percent or certainly well over 60-70 percent of that surface.”

From some of the tunicates, the researchers discovered a compound that in the laboratory, in early studies, has been shown to combat some forms of melanoma in mice.

SOUNDBITE: Jim McClintock, Marine Chemical Ecologist, UAB: “We certainly have the potential of discovering a compound that could help fight cancer, or AIDS or a flu virus, these types of things.”

Because the water is so cold, the researchers’ dives are limited to 30-40 minutes at a time. They wear thick layers of underwear under dry suits, but their hands do get cold.

SOUNDBITE: Chuck Amsler, Phycologist, Univ. of Alabama at Birmingham: “Unfortunately, if we wore as much on our hands as we wore everywhere else, we’d be wearing boxing gloves and we wouldn’t get a lot of work done. So you’re hands get cold. We have some tricks, and chemical heater packs on the hands are nice.”

Their primary goal on these dive studies is to find out more about the ecosystems in these underwater forests, and learn about the relationships between the creatures and plants that live there.

The University of Alabama at Birmingham in Antarctica expedition is funded by the National Science Foundation.

The Seitaad ruessi fossil, described in the journal PLoS One, is a relative of the long-necked sauropods that were once Earth's biggest animals.

The Seitaad ruessi fossil, described in the journal PLoS One, is a relative of the long-necked sauropods that were once Earth's biggest animals.S. ruessi, found in what is now Utah, could have walked on all four legs, or risen up to walk on just two.

It is from the Early Jurassic period, between 175 and 200 million years ago.

At that time, all of Earth's continents were still joined in the super-continent Pangaea, and sauropodomorphs like S. ruessi have been found in South America and Africa.

Unlike the sauropods to which they are related, S. ruessi was relatively small, about a metre tall and 3.5-4m long with its lengthy neck and tail, weighing in at between 70 and 90kg.

Plant life

Plant lifeMuch of the fossil, first discovered by a local artist in 2004, was perfectly preserved in sandstone. However, it is missing its head, neck and tail.

Joseph Sertich of the University of Utah and Mark Loewen from the Utah Museum of Natural History have since then worked to free S. ruessi from its sandy grave - in an arid part of the US that, 185 million years ago, formed part of a huge desert.

"Although Seitaad was preserved in a sand dune, this ancient desert must have included wetter areas with enough plants to support these smaller dinosaurs and other animals," said Mr Sertich.

"Just like in deserts today, life would have been difficult in Utah's ancient 'sand sea.'"

Dr Grigori Perelman, who has been dubbed "the smartest man in the world", refused the money, despite living in poverty in a cockroach-infested flat in St Petersburg.

Dr Grigori Perelman, who has been dubbed "the smartest man in the world", refused the money, despite living in poverty in a cockroach-infested flat in St Petersburg.When told of the prize, which was offered by the Clay Mathematics Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts to anyone who could solve the conundrum, the Daily Mail reports that he refused to open the door, saying only: "I don't need anything. I have all I want."

The Poincare Conjecture basically asserts that any three-dimensional space without holes in it is equivalent to a stretched sphere and had confounded maths experts for more than a century.

But in 2003 Mr Perelman, who was working as a researcher at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics in St Petersburg, began posting papers on the internet suggesting he had solved the puzzle.

Rigorous tests proved he was correct.

Rigorous tests proved he was correct.But the bearded genius, 44, is known for his hatred of the limelight.

Four years ago, after posting his solution on the web, he failed to turn up to receive his prestigious Fields Medal from the International Mathematical Union in Madrid.

At the time he stated: "I'm not interested in money or fame. I don't want to be on display like an animal in a zoo.

"I'm not a hero of mathematics. I'm not even that successful, that is why I don't want to have everybody looking at me."

His friends now say he has given up mathematics.

Neighbours say Perelman spends his days inside the cockroach-ridden flat playing table tennis against a wall.

The suspected temperate nature of the planet — whose surface temperature is somewhere between minus 4 and plus 360 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 20 and plus 160 degrees Celsius) — could mean that it it could have liquid water.

The suspected temperate nature of the planet — whose surface temperature is somewhere between minus 4 and plus 360 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 20 and plus 160 degrees Celsius) — could mean that it it could have liquid water.But this water wouldn't be in the form of Earth-like oceans, more likely it would be only in the form of clouds with water droplets, said Tristan Guillot, a member of the team that discovered the planet.

Astronomers announced the discovery of the planet, dubbed CoRoT-9b, last week, when they described it as a Jupiter-sized world that orbits its parent star at about the orbit of Mercury in our solar system.

This distance, while it seems close to the star, is considerably further out than many other known Jupiter-sized exoplanets, which means that CoRoT-9b likely escapes the wild temperature extremes experienced by those planets.

Such an example of this can be seen in our own solar system, again on Jupiter.

"The same is true for Jupiter, which actually has water clouds, but they're hidden from view in the deep atmosphere," Guillot told SPACE.com in an e-mail.

Water oceans are out of the question because gas giant planets "don't have any surface: one goes continuously from the atmosphere to a progressively denser environment in the interior," Guillot said.

The interior of the planet would look something like this:

"In the very deep interior, there may be a core made of water compressed to extremely high pressures (10 million times the atmospheric pressure and more) and temperatures [of about] 30,000 Kelvins (or Celsius) [54,000 degrees Fahrenheit]; water is then expected to become a ionized plasma, behaving a bit like a liquid," Guillot explained. "But calling it an ocean would be far-stretched."

Another possibility for water in this new planetary system would be the presence of a moon.

If the temperatures at CoRoT-9b's orbit are in the right range, an ice-ball moon could exist, like Saturn's moon Titan, or possibly even a moon with liquid oceans.

"Titan-like moons with dense atmospheres and liquid water on the surface may exist there," said Hans Deeg, another member of the team that discovered the planet.

The SpaceShipTwo rocket plane is attached between the twin fuselages of its

The SpaceShipTwo rocket plane is attached between the twin fuselages of its WhiteKnightTwo carrier airplane, as seen from below during Monday's test flight

from California's Mojave Air and Space Port.

The craft, which has been christened the VSS Enterprise, remained firmly attached to its WhiteKnightTwo carrier airplane throughout the nearly three-hour test flight. It will take many months of further tests before SpaceShipTwo actually goes into outer space. Nevertheless, today's outing marks an important milestone along a path that could take paying passengers to the final frontier as early as 2011 or 2012.

The captive-carry flight comes three and a half months after SpaceShipTwo's unveiling in Mojave. The project, backed by British billionaire Richard Branson, builds upon the first-ever private-sector spaceflights, flown five years ago by the SpaceShipOne prototype plane. Both SpaceShipOne and SpaceShipTwo were designed by aerospace guru Burt Rutan.

Today's test was the first in a series aimed at checking the aerodynamics of the rocket plane in a controlled, real-world environment. The configuration for SpaceShipTwo is significantly different from that for SpaceShipOne (which is now hanging in the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum) and its WhiteKnightOne mothership. SpaceShipOne was slung right beneath WhiteKnightOne's fuselage, while SpaceShipTwo rides between WhiteKnightTwo's twin fuselages.

Virgin Galactic's spaceflight profile calls for the rocket to be taken up to around 50,000 feet in altitude, where it would be released from the mothership. SpaceShipTwo would then fire up its own rocket engine for the final push to space. But for these initial captive-carry tests, the rocket plane will stay attached to WhiteKnightTwo.

Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo rocket plane takes to the air for a test flight on

Virgin Galactic's SpaceShipTwo rocket plane takes to the air for a test flight on Monday, firmly connected to its WhiteKnightTwo carrier airplane.

When Rutan and his team are confident that they've tweaked the design to optimize its flightworthiness, they'll move on to the next phase of testing: unpowered glide tests, during which WhiteKnightTwo will release SpaceShipTwo (and its pilot) for a gliding flight back down to the Mojave runway.

That phase will lead to an even more ambitious series of flights, scheduled to start next year, during which SpaceShipTwo will light up its hybrid rocket engine. Eventually those powered test flights will push the plane beyond the sound barrier - and beyond the 100-kilometer (62-mile) altitude mark that serves as the internationally accepted boundary of outer space.

Passenger operations won't begin until a goodly number of test flights have broken the space barrier. No firm date has been set, but the conventional wisdom is currently focusing on late 2011 or early 2012. "Test flights will pace the program," Virgin Galactic's operations manager, Julie Tizard, said last year at a spaceflight conference in New Mexico.

Virgin Galactic's test program is being conducted out of Mojave, where Rutan's Scaled Composites has its home base. However, the passenger flights will likely be run out of New Mexico's Spaceport America, which is currently under construction.

Executives at Virgin Galactic have consistently said no paying passengers will be taken on until they're confident that the flights measure up to their safety standards. Branson and his family are to be among the first spacefliers.

More than 330 people have already put down deposits toward the $200,000 fare for a tour package - an adventure that will feature a rocket-powered roller-coaster ride, several minutes of weightlessness, and a commanding view of the curving Earth beneath the blackness of space.

An in-flight closeup shows SpaceShipTwo riding between WhiteKnightTwo's twin

An in-flight closeup shows SpaceShipTwo riding between WhiteKnightTwo's twin fuselages. This SpaceShipTwo plane has been christened the Enterprise, and the

WhiteKnightTwo is named Eve, after Virgin founder Richard Branson's mother.

Click on the picture for a larger view that clearly shows the "Eve" mascots.

Here's the full news release from Virgin Galactic, with quotes from Rutan and Branson:

"Virgin Galactic announced today that its commercial manned spaceship, VSS Enterprise, this morning successfully completed its first 'captive carry' test flight, taking off at 07:05 am (PST) from Mojave Air and Spaceport, California. "The spaceship was unveiled to the public for the first time on December 7th 2009 and named by Governors [Arnold] Schwarzenegger [of California] and [New Mexico's Bill] Richardson. VSS Enterprise remained attached to its unique WhiteKnightTwo carrier aircraft, VMS Eve, for the duration of the 2 hours 54 minutes flight, achieving an altitude of 45,000 feet (13716 meters). "Both vehicles are being developed for Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, by Mojave based Scaled Composites. Founded by Burt Rutan, Scaled developed SpaceShipOne which in 2004 claimed the $10 million Ansari X Prize as the world’s first privately developed manned spacecraft. Virgin Galactic’s new vehicles share much of the same basic design but are being built to carry six fare-paying passengers on suborbital space flights, allowing an out-of-the-seat zero gravity experience and offering astounding views of the planet from the black sky of space. "Virgin Galactic has already taken around $45 million in deposits for spaceflight reservations from over 330 people wanting to experience space for themselves. "The first flight of VSS Enterprise is another major milestone in an exhaustive flight testing program, which started with the inaugural flight of VMS Eve in 2008 and is at the heart of Virgin Galactic’s commitment to safety. "Commenting on the historic flight, Burt Rutan said: 'This is a momentous day for the Scaled and Virgin Teams. The captive-carry flight signifies the start of what we believe will be extremely exciting and successful spaceship flight test program.' "Sir Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Galactic, added: 'Seeing the finished spaceship in December was a major day for us, but watching VSS Enterprise fly for the first time really brings home what beautiful, ground-breaking vehicles Burt and his team have developed for us. It comes as no surprise that the flight went so well; the Scaled team is uniquely qualified to bring this important and incredible dream to reality. Today was another major step along that road and a testament to US engineering and innovation.' "The VSS Enterprise test flight program will continue though 2010 and 2011, progressing from captive carry to independent glide and then powered flight, prior to the start of commercial operations."

Virgin Galactic's business plan calls for building five SpaceShipTwo planes and two WhiteKnightTwo carriers, with options for more.

The study finds that "domes" of carbon dioxide (CO2) over cities have potentially deadly health effects, when compared to CO2 over rural areas. What happens is that the excess CO2 in cities causes local temperatures to rise, which in turn causes unhealthy local air pollutants and ground-level ozone already present to increase as well.

The study finds that "domes" of carbon dioxide (CO2) over cities have potentially deadly health effects, when compared to CO2 over rural areas. What happens is that the excess CO2 in cities causes local temperatures to rise, which in turn causes unhealthy local air pollutants and ground-level ozone already present to increase as well."Not all carbon dioxide emissions are equal," said Jacobson.

Jacobson estimates the additional carbon dioxide could cause about 300 to 1,000 deaths per year across the USA. These deaths are in addition to those that would be caused by regular air pollution, which are roughly 50,000 to 100,000 per year.

The study is the first to look at the health impacts of increasing CO2 above cities.

"If correct," according to the paper, "this result contradicts the basis for air pollution regulations worldwide, none of which considers controlling local CO2 based on its local health impacts."

"If correct," according to the paper, "this result contradicts the basis for air pollution regulations worldwide, none of which considers controlling local CO2 based on its local health impacts."Additionally, Jacobson says this provides a scientific basis for regulating CO2 at the local level, and that the cap-and-trade proposal currently under consideration by the U.S. Senate is flawed.

"The cap-and-trade proposal assumes there is no difference in the impact of carbon dioxide, regardless of where it originates," Jacobson said. "This study contradicts that assumption."

"It doesn't mean you can never do something like cap and trade," he added. "It just means that you need to consider where the CO2 emissions are occurring."

The results of the study appear in a paper published online by the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Science and Technology.

Japan, which imports about 80% of bluefin for sushi and sashimi, led those opposed to the ban. Many developing countries voted against it due to fears it would affect their fishing economies, the Associated Press reported from Doha, Qatar, where the meeting is taking place.

Only the United States, Norway and Kenya supported the proposal. It can still be reconsidered at the final plenary session on Thursday, March 25.

Only the United States, Norway and Kenya supported the proposal. It can still be reconsidered at the final plenary session on Thursday, March 25.Conservation and fisheries groups have argued that the large, migratory fish need protection because their populations have fallen as much as 75% due to overfishing.

"The market for this fish is just too lucrative and the pressure from fishing interests too great, for enough governments to support a truly sustainable future for the fish," Susan Lieberman, director of international policy for the Pew Environment Group, said in a statement.

With no ban, the tuna will be regulated by the group that has long overseen their trade, the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas, or ICCAT.

Monaco and conservation groups said that historically ICCAT's quotas had been too high to allow the fish stocks to replenish.

"Today's vote puts the fate of Atlantic bluefin tuna back in the hands of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), the very body that drove the species to the disastrous state it is now in," Lieberman said.

The delegates also rejected a U.S. proposal to ban the international sale of polar bear skins and parts. Canada and Greenland in turn said that a small enough number of polar bears are killed and thus wouldn't affect the population as a whole, while potentially devastating indigenous communities that rely on polar bear hunts for money.

U.S. delegates said that hunting only compounded the difficulties faced by the bears as their habitat degrades with climate change. By some projections, the iconic animals could decline by as much as two-thirds by 2050.

No sign of Avatar's blue-skinned Na'vi aliens, but Europe's CoRoT space telescope Wednesday yielded the discovery of a Jupiter-sized world orbiting a "temperate" distance from its star.

The discovery marks the first "transit" detection, where the dip in starlight caused by a planet orbiting in front of its star tips off astronomers to its existence.

"Our discovery proves that the transit-method is able to find also longer-period planets," says Spain's Hans Deeg of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Tenerife, lead author of the report in the Nature journal. "The most exciting discoveries by transits are still to come."

First detected in 2008, the newly-reported planet, CoRot-9b, is about 0.84 times as heavy as Jupiter, and circles its star once every 95 days, meaning it experiences temperatures ranging from -10 to 314 degrees Fahrenheit, balmy by solar system standards. Several other worlds have been detected indirectly in such temperate orbits by measuring the gravitational wobbles they induce in their stars, but this is the first transit detection of one, says study co-author Didier Queloz of Switzerland's Observatoire de l'Universite´ de Geneve. That means CoRot-9b offers an opportunity to study its atmosphere by examination of the chemicals revealed in the spectra of its light.

"This one looks like another "warm Jupiter" on a relatively long period orbit," says planetary scientist Alan Boss of the Carnegie Institute of Washington (D.C.) "It is good to hear that CoRoT is still finding new transiting planets -- it has been a while since they have announced any new discoveries."

In theory, such a planet could have a moon with liquid water on its surface:

A moon could in principle be orbiting this planet; one can also calculate that is has to be on an orbit with a period shorter than 9 days. If such a moon would be very large (more than ~5

Earth radii), it should even have been detected in the current data; since this wasn't the case, we can exclude this. So, Titan-like moons are possible; though with surface temperatures that are much higher: the so-called effective temperature should be similar to the planet, (-20 to 150C, depending on the albedo) but real surface temperatures can be expected to be significantly higher due to Green-house effects; though a priori we can't exclude temperatures or conditions compatible with life on such a moon. "Sorry, I didn't see Avatar yet," Deeg adds. NASA's current Kepler space telescope mission, which will examine stars for transit planets out to about 3,000 light years away (one light year is about 5.9 trillion miles) in one direction of the Milky Way Galaxy, should yield many more planets resenbling CoRoT-9b, Deeg suggests, particularly given the positive results from the smaller CoRoT telescope.

Earth radii), it should even have been detected in the current data; since this wasn't the case, we can exclude this. So, Titan-like moons are possible; though with surface temperatures that are much higher: the so-called effective temperature should be similar to the planet, (-20 to 150C, depending on the albedo) but real surface temperatures can be expected to be significantly higher due to Green-house effects; though a priori we can't exclude temperatures or conditions compatible with life on such a moon. "Sorry, I didn't see Avatar yet," Deeg adds. NASA's current Kepler space telescope mission, which will examine stars for transit planets out to about 3,000 light years away (one light year is about 5.9 trillion miles) in one direction of the Milky Way Galaxy, should yield many more planets resenbling CoRoT-9b, Deeg suggests, particularly given the positive results from the smaller CoRoT telescope.

The 2010 report, commissioned and coordinated by the Whitehorse, Yukon–based Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP), was presented Wednesday at the State of the Arctic Conference in Miami. It covers 965 populations of 365 species, representing 35 percent of all known vertebrate species found in the Arctic.

The Arctic region is broken into three floristic zones (High, Low and Sub Arctic), referring to the amount of plant life that exists within the regions' boundaries.

Outside of the High Arctic, the news wasn't all bad: The study found that Low Arctic species populations increased 46 percent between 1970 and 2004 (aided by several conservation efforts, such as tighter restrictions on hunting bowhead whales), whereas Sub Arctic populations remained stable during that time period.

Among the specific findings: Low Arctic fish species such as pollack have benefited from rising ocean temperatures, which is why their populations have increased. Populations of lemmings, caribou and red knot (a shorebird) have all decreased. Migratory birds that pass through the Arctic have decreased an average of 6 percent, although that number is skewed by a "dramatic increase" in some populations of migratory geese.Furthermore, brown bear populations have dropped as much as 50 percent in the last 15 years.

Among the specific findings: Low Arctic fish species such as pollack have benefited from rising ocean temperatures, which is why their populations have increased. Populations of lemmings, caribou and red knot (a shorebird) have all decreased. Migratory birds that pass through the Arctic have decreased an average of 6 percent, although that number is skewed by a "dramatic increase" in some populations of migratory geese.Furthermore, brown bear populations have dropped as much as 50 percent in the last 15 years.The report avoids direct mention of polar bear populations, but notes that the greatest losses in Arctic sea ice on which the polar bear relies occurred in 2008 and 2009, outside the range of this study.

The CBMP is now calling for increased efforts to count and catalogue Arctic species because many, especially those in the High Arctic, lack detailed population indices.

The effort focused on the south pole, with its larger and deeper craters, but last week, scientists reported there is also ice in craters near the north pole.

And not just a dusting of frost. Within 40 small craters, one to nine miles wide, they estimated 600 million metric tons of water. Perhaps most notably, “It has to be relatively pure,” said Paul Spudis, the principal investigator for the instrument that made the discovery.

That is significant, because the ice in these craters could be easily tapped by future lunar explorers — not just for drinking water, but also broken apart into oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for fuel. In the previous findings, scientists could not rule out the possibility that the water was sparse or locked up within rocks and difficult to extract.

In this case, the evidence comes from radar signals bounced off the moon’s surface by a NASA-built instrument that flew aboard India’s Chandrayaan-1 moon probe, which was launched in 2008 and operated until last August. The reflections contain a telltale signature when they pass through transparent ice. If too much dirt and rocks are mixed in, the signature vanishes, and even permafrost, which typically contains 10 to 50 percent water, does not exhibit signs of water in the radar reflections.

Dr. Spudis, a scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, said he guessed the water ice in the north polar craters might be 90 percent pure. He said the team was currently analyzing data covering the south pole craters.

The findings were reported at the Lunar and Planetary Science conference last week and will appear in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

A similar experiment in 1994 aboard the Clementine probe, a joint effort between NASA and the Department of Defense, first revealed hints of water ice near the south pole, but the interpretation of the data remained controversial. The newer instrument is much more sensitive, and another copy of the experiment is currently operating aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

In addition to the water near the poles, scientists also reported that a very thin layer of water covers much of the lunar surface. Water, it appears, not only exists, but is also moving around. “The moon is working in a way you didn’t expect,” Dr. Spudis said.

Michael Clair, who practiced in Fall River but now lives in Maryland, is charged with assault and battery, larceny, submitting false claims to Medicaid and illegally prescribing drugs, the Associated Press writes.

Medicaid — the federal health plan for the poor — suspended Clair in 2002, prosecutors said, but he allegedly hired other dentists for his clinic and filed claims using their numbers between August 2003 and June 2005.

Add plumbing to the mysterious arts of the ancient Maya, investigators report. In a Journal of Archaeological Science study, anthropologist Kirk French and civil engineer Christopher Duffy of Penn State report on a conduit designed to deliver pressurized water to Palenque, an urban center in southern Mexico, more than 1,400 years ago.

Add plumbing to the mysterious arts of the ancient Maya, investigators report. In a Journal of Archaeological Science study, anthropologist Kirk French and civil engineer Christopher Duffy of Penn State report on a conduit designed to deliver pressurized water to Palenque, an urban center in southern Mexico, more than 1,400 years ago."The ancient Maya are renowned as great builders, but are rarely regarded as great engineers. Their constructions, though often big and impressive, are generally considered unsophisticated," say the study authors. However, they add, "(m)any Maya centers exhibit sophisticated facilities that captured, routed, stored, or otherwise manipulated water for various purposes."

Palenque, founded around 100 A.D., grew to some 1,500 temples, homes and palaces by 800 A.D., under a series of powerful rulers. "With 56 springs, nine perennial waterways, aqueducts, pleasure pools, dams, and bridges – the city truly lived up to its ancient name, Lakamha' or "Big Water"," says the study.

Excavations reveal the 217-foot-long, spring-fed "Piedras Bolas" aqueduct underneath Palenque was designed to narrow at its end, producing a high-pressure fountain. It's the first example of

deliberately-engineered hydraulic pressure in the New World, prior to the arrival of the conquistadors in the 1,500's. Now eroded, the conduit dates from 250 A.D. to 600 A.D.

deliberately-engineered hydraulic pressure in the New World, prior to the arrival of the conquistadors in the 1,500's. Now eroded, the conduit dates from 250 A.D. to 600 A.D."Palenque is unique in that it is a major center where the Maya built water systems to drain water away from the site," says archaeologist Lisa Lucero of the University of Illinois, by email. Most Maya centers stored water in reservoirs for the winter dry season. "Palenque, thus, is a unique site; we would not expect to find such water systems elsewhere. That said, there is lots of lit on the different kinds of water systems. For example, all centers with large plazas have drainage systems to keep the plazas dry during rain. "

The conduit lay underneath several households and could have stored water during the dry season, suggest the study authors. Another possibility, the conduit's flow may have, "created the pressure necessary for an aesthetically pleasing fountain, and perhaps served as an aid in the filling of water jars."

Archaeologists may have missed such technology elsewhere, concludes the study, not giving the ancients enough credit. " It is likely that there are other examples of Precolumbian water pressure throughout the Americas that have been misidentified or unassigned. The most promising candidate being the segmented ceramic tubing found at several sites throughout central Mexico," they suggest.

Six hundred feet below the ice where no light shines, scientists had figured nothing much more than a few microbes could exist.

Six hundred feet below the ice where no light shines, scientists had figured nothing much more than a few microbes could exist.

That's why a NASA team was surprised when they lowered a video camera to get the first long look at the underbelly of an ice sheet in Antarctica. A curious shrimp-like creature came swimming by and then parked itself on the camera's cable. Scientists also pulled up a tentacle they believe came from a foot-long jellyfish.

"We were operating on the presumption that nothing's there," said NASA ice scientist Robert Bindschadler, who will be presenting the initial findings and a video at an American Geophysical Union meeting Wednesday. "It was a shrimp you'd enjoy having on your plate."

"We were just gaga over it," he said of the 3-inch-long, orange critter starring in their two-minute video. Technically, it's not a shrimp. It's a Lyssianasid amphipod, which is distantly related to shrimp.

The video is likely to inspire experts to rethink what they know about life in harsh environments. And it has scientists musing that if shrimp-like creatures can frolic below 600 feet of Antarctic ice in subfreezing dark water, what about other hostile places? What about Europa, a frozen moon of Jupiter?

"They are looking at the equivalent of a drop of water in a swimming pool that you would expect nothing to be living in and they found not one animal but two," said biologist Stacy Kim of the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories in California, who joined the NASA team later. "We have no idea what's going on down there."

Microbiologist Cynan Ellis-Evans of the British Antarctic Survey called the finding intriguing.

"This is a first for the sub-glacial environment with that level of sophistication," Ellis-Evans said. He said there have been findings somewhat similar, showing complex life in retreating ice shelves, but nothing quite directly under the ice like this.

Ellis-Evans said it's possible the creatures swam in from far away and don't live there permanently.

But Kim, who is a co-author of the study, doubts it. The site in West Antarctica is at least 12 miles from open seas. Bindschadler drilled an 8-inch-wide hole and was looking at a tiny amount of water. That means it's unlikely that that two critters swam from great distances and were captured randomly in that small of an area, she said.

Yet scientists were puzzled at what the food source would be for these critters. While some microbes can make their own food out of chemicals in the ocean, complex life like the amphipod can't, Kim said.

So how do they survive? That's the key question, Kim said.

"It's pretty amazing when you find a huge puzzle like that on a planet where we thought we know everything," Kim said.

The U-M system's processor, solar cells, and battery are all contained in its tiny frame, which measures 2.5 by 3.5 by 1 millimeters. It is 1,000 times smaller than comparable commercial counterparts.

The system could enable new biomedical implants as well as home-, building- and bridge-monitoring devices. It could vastly improve the efficiency and cost of current environmental sensor networks designed to detect movement or track air and water quality.

With an industry-standard ARM Cortex-M3 processor, the system contains the lowest-powered commercial-class microcontroller. It uses about 2,000 times less power in sleep mode than its most energy-efficient counterpart on the market today.

The engineers say successful use of an ARM processor-- the industry's most popular 32-bit processor architecture-- is an important step toward commercial adoption of this technology.

Greg Chen, a computer science and engineering doctoral student, will present the research Feb. 9 at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference in San Francisco.

"Our system can run nearly perpetually if periodically exposed to reasonable lighting conditions, even indoors," said David Blaauw, an electrical and computer engineering professor. "Its only limiting factor is battery wear-out, but the battery would last many years."

"The ARM Cortex-M3 processor has been widely adopted throughout the microcontroller industry for its low-power, energy efficient features such as deep sleep mode and Wake-Up Interrupt Controller, which enables the core to be placed in ultra-low leakage mode, returning to fully active mode almost instantaneously," said Eric Schorn, vice president, marketing, processor division, ARM. "This implementation of the processor exploits all of those features to the maximum to achieve an ultra-low-power operation."

The sensor spends most of its time in sleep mode, waking briefly every few minutes to take measurements. Its total average power consumption is less than 1 nanowatt. A nanowatt is one-billionth of a watt.

The developers say the key innovation is their method for managing power. The processor only needs about half of a volt to operate, but its low-voltage, thin-film Cymbet battery puts out close to 4 volts. The voltage, which is essentially the pressure of the electric current, must be reduced for the system to function most efficiently.

"If we used traditional methods, the voltage conversion process would have consumed many times more power than the processor itself uses," said Dennis Sylvester, an associate professor in electrical and computer engineering.

One way the U-M engineers made the voltage conversion more efficient is by slowing the power management unit's clock when the processor's load is light.

"We skip beats if we determine the voltage is sufficiently stable," Sylvester said.

The designers are working with doctors on potential medical applications. The system could enable less-invasive ways to monitor pressure changes in the eyes, brain, and in tumors in patients with glaucoma, head trauma, or cancer. In the body, the sensor could conceivably harvest energy from movement or heat, rather than light, the engineers say.

The inventors are working to commercialize the technology through a company led by Scott Hanson, a research fellow in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

The paper is entitled "Millimeter-Scale Nearly Perpetual Sensor System with Stacked Battery and Solar Cells."

This research is funded by the National Science Foundation, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the Focus Center Research Program and ARM.

His first response was disbelief:

While multicolored birds will often show some variation, Dr. Baker explains that what makes this all-black King Penguin so rare is that the bird's melanin deposits have occurred where they are typically not present -- enough so that no light feathers even checker the bird's normally white chest.

Andrew Evans:

Melanism is merely the dark pigmentation of skin, fur -- or in this case, feathers. The unique trait derives from increased melanin in the body. Genes may play a role, but so might other factors. While melanism is common in many different animal species (e.g., Washington D.C. is famous for its melanistic squirrels), the trait is extremely rare in penguins. All-black penguins are so rare there is practically no research on the subject -- biologists guess that perhaps one in every quarter million of penguins shows evidence of at least partial melanism, whereas the penguin we saw appears to be almost entirely (if not entirely) melanistic.

Whether or not the all-black look catches on in the penguin fashion world, it's nice to see someone dressing-down for once.

Grandmother Zhang Ruifang, 101, of Linlou village, Henan province, began developing the mysterious protrusion last year.

Since then it has grown 2.4in in length and another now appears to emerging on the other side of the mother of seven’s forehead.

The condition has left her family baffled and worried.

Her youngest of six sons, Zhang Guozheng, 60, said when a patch of rough skin formed on her forehead last year ‘we didn't pay too much attention to it’.

‘But as time went on a horn grew out of her head and it is now 6cm long,' added Mr Zhang, whose eldest brother and sibling is 82 years old.

‘Now something is also growing on the right side of her forehead. It’s quite possible that it’s another horn.’

Although, it is unknown what the protrusion is on Mrs Zhang’s head, it resembles a cutaneous horn.

This is a funnel-shaped growth and although most are only a few millimetres in length, some can extend a number of inches from the skin.

Cutaneous horns are made up of compacted keratin, which is the same protein we have in our hair and nails, and forms horns, wool and feathers in animals.

They usually develop in fair-skinned elderly adults who have a history of significant sun exposure but it is extremely unusual to see it form protrusions of this size.

The growths are most common in elderly people, aged between 60 and the mid-70s. They can sometimes be cancerous but more than half of cases are benign.

Common underlying causes of cutaneous horns are common warts, skin cancer and actinic keratoses, patches of scaly skin that develop on skin exposed to the sun, such as your face, scalp or forearms.

Cutaneous horns can be removed surgically but this does not treat the underlying cause.

They warn that the oceans' complex undersea ecosystems and fragile food chains could be disrupted.

They warn that the oceans' complex undersea ecosystems and fragile food chains could be disrupted.

In some spots off Washington state and Oregon , the almost complete absence of oxygen has left piles of Dungeness crab carcasses littering the ocean floor, killed off 25-year-old sea stars, crippled colonies of sea anemones and produced mats of potentially noxious bacteria that thrive in such conditions.

Areas of hypoxia, or low oxygen, have long existedin the deep ocean. These areas — in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans — appear to be spreading, however, covering more square miles, creeping toward the surface and in some places, such as the Pacific Northwest , encroaching on the continental shelf within sight of the coastline.

"The depletion of oxygen levels in all three oceans is striking," said Gregory Johnson , an oceanographer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Seattle .

In some spots, such as off the Southern California coast, oxygen levels have dropped roughly 20 percent over the past 25 years. Elsewhere, scientists say, oxygen levels might have declined by one-third over 50 years.

"The real surprise is how this has become the new norm," said Jack Barth , an oceanography professor at Oregon State University . "We are seeing it year after year."

Barth and others say the changes are consistent with current climate-change models. Previous studies have found that the oceans are becoming more acidic as they absorb more carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

"If the Earth continues to warm, the expectation is we will have lower and lower oxygen levels," said Francis Chan , a marine researcher at Oregon State .

As ocean temperatures rise, the warmer water on the surface acts as a cap, which interferes with the natural circulation that normally allows deeper waters that are already oxygen-depleted to reach the surface. It's on the surface where ocean waters are recharged with oxygen from the air.

Commonly, ocean "dead zones" have been linked to agricultural runoff and other pollution coming down major rivers such as the Mississippi or the Columbia . One of the largest of the 400 or so ocean dead zones is in the Gulf of Mexico , near the mouth of the Mississippi .

Commonly, ocean "dead zones" have been linked to agricultural runoff and other pollution coming down major rivers such as the Mississippi or the Columbia . One of the largest of the 400 or so ocean dead zones is in the Gulf of Mexico , near the mouth of the Mississippi .

However, scientists now say that some of these areas, including those off the Northwest, apparently are linked to broader changes in ocean oxygen levels.

The Pacific waters off Washington and Oregon face a double whammy as a result of ocean circulation.

Scientists have long known of a natural low-oxygen zone perched in the deeper water off the Northwest's continental shelf.

During the summer, northerly winds aided by the Earth's rotation drive surface water away from the shore. This action sucks oxygen-poor water to the surface in a process called upwelling.

Though the water that's pulled up from the depths is poor in oxygen, it's rich in nutrients, which fertilize phytoplankton. These microscopic organisms form the bottom of one of the richest ocean food chains in the world. As they die, however, they sink and start to decay. The decaying process uses oxygen, which depletes the oxygen levels even more.

Though the water that's pulled up from the depths is poor in oxygen, it's rich in nutrients, which fertilize phytoplankton. These microscopic organisms form the bottom of one of the richest ocean food chains in the world. As they die, however, they sink and start to decay. The decaying process uses oxygen, which depletes the oxygen levels even more.

Southerly winds reverse the process in what's known as down-welling.

Changes in the wind and ocean circulation since 2002 have disrupted what had been a delicate balance between upwelling and down-welling. Scientists now are discovering expanding low-oxygen zones near shore.

"It is consistent with models of global warming, but the time frame is too short to know whether it is a trend or a weather phenomenon," Johnson said.

Others were slightly more definitive, quicker to link the lower oxygen levels to global warming rather than to such weather phenomena as El Nino or the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a shift in the weather that occurs every 20 to 30 years in the northern oceans.

"It's a large disturbance in the ecosystem that could have huge biological changes," said Steve Bograd , an oceanographer at NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center in Southern California .

Bograd has been studying oxygen levels in the California Current, which runs along the West Coast from the Canadian border to Baja California and, some scientists think, eventually could be affected by climate change.

Bograd has been studying oxygen levels in the California Current, which runs along the West Coast from the Canadian border to Baja California and, some scientists think, eventually could be affected by climate change.

So far, the worst hypoxic zone off the Northwest coast was found in 2006. It covered nearly 1,200 square miles off Newport, Ore. , and according to Barth it was so close to shore you could hit it with a baseball. The zone covered 80 percent of the water column and lasted for an abnormally long four months.

Because of upwelling, some of the most fertile ocean areas in the world are found off Washington and Oregon . Similar upwelling occurs in only three other places, off the coast of Peru and Chile , in an area stretching from northern Africa to Portugal and along the Atlantic coast of South Africa and Namibia .

Scientists are unsure how low oxygen levels will affect the ocean ecosystem. Bottom-dwelling species could be at the greatest risk because they move slowly and might not be able to escape the lower oxygen levels. Most fish can swim out of danger. Some species, however, such as chinook salmon, may have to start swimming at shallower depths than they're used to. Whether the low oxygen zones will change salmon migration routes is unclear.

Scientists are unsure how low oxygen levels will affect the ocean ecosystem. Bottom-dwelling species could be at the greatest risk because they move slowly and might not be able to escape the lower oxygen levels. Most fish can swim out of danger. Some species, however, such as chinook salmon, may have to start swimming at shallower depths than they're used to. Whether the low oxygen zones will change salmon migration routes is unclear.

Some species, such as jellyfish, will like the lower-oxygen water. Jumbo squid, usually found off Mexico and Central America , can survive as oxygen levels decrease and now are found as far north as Alaska .

"It's like an experiment," Chan said. "We are pulling some things out of the food web and we will have to see what happens. But if you pull enough things out, it could have a real impact."